In 100 years, passport discrimination will be seen as wrong as skin-colour discrimination

September 2020

It's 2020, and you're browsing the web when you see a job ad with something very unusual:

"We're looking for experienced marketers to help us launch a new product line. White candidates only, please".

Infuriating and depressing! How long do you think it would take for every news agency in the world to be talking about this? And for this company to go out of business? And how about for the authors to be facing criminal charges?

This entire situation sounds very unlikely to happen today. But isn't it disturbing to think that less than a century ago this would be just another ordinary day?

Now, replace the "White candidates only" with "Australian residents only", and you have a real example of thousands of modern job ads shared around the web every day.

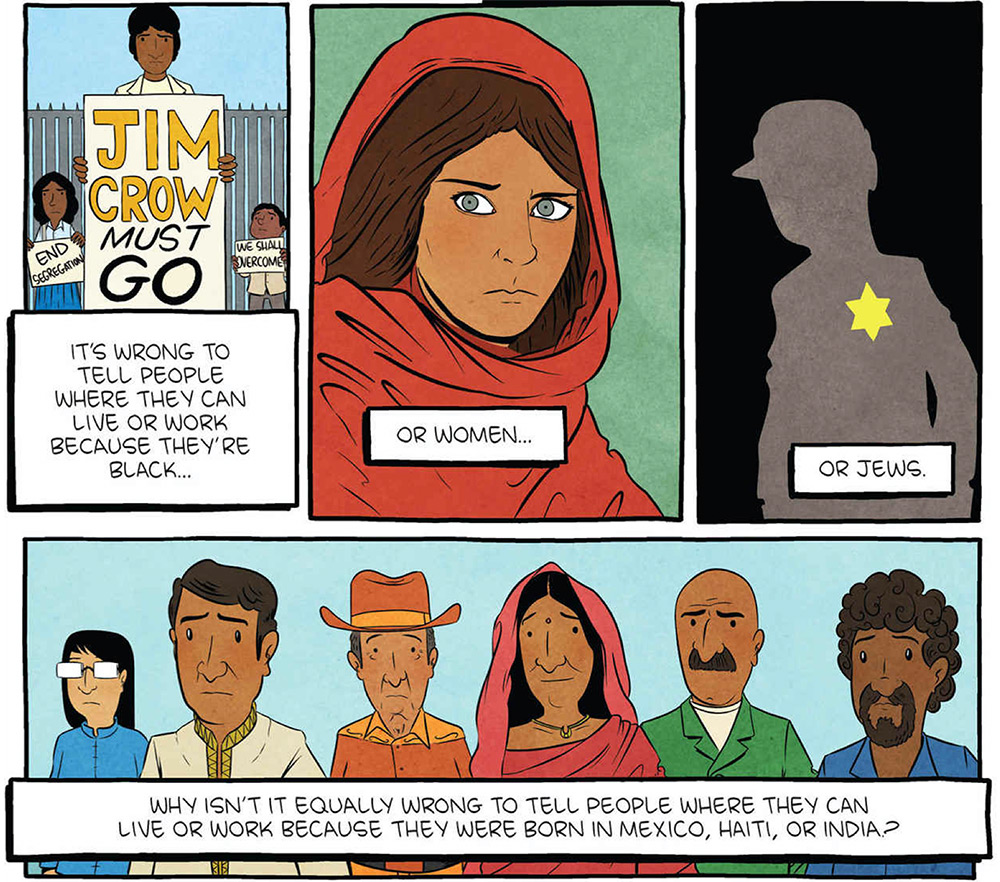

(Illustration from the book Open Borders by Bryan Caplan and Zach Weinersmith)

I was born in Brazil, and as I grew up, I became each year more distant and frustrated with the country's (and my) future. Living in one of the poorest states in the country, I was one of the very few who was lucky and privileged to have parents who could afford to send me for a year abroad during high-school.

I spent my last year of high school in the U.S., a life-changing and mind-expanding event. With one caveat, though. I wasn't allowed to work and get paid anywhere while I was in the country. I still remember my American friends giving me a ride on their way to work after school and perplexed that I depended on my parents sending me money from overseas.

Back in Brazil, as I entered university and started working as a software developer, I found myself dreaming about working and living in Australia. But once again, I wasn't allowed, I was born in Brazil.

As an 18-year old, my obsession with moving to Australia wasn't just rational. It was also an emotional one. I knew I wanted to scape the fear of daily violence in Brazil. I dreamed about a society with less economic inequality. But I also pictured myself surfing in Australian waves.

And to be fair, I didn't understand what was wrong with that. I wanted a better life right away. A better life obviously means different things for different people. For me, I knew it would be a move to Australia. But I couldn't just save some money, buy a ticket and fly to Oceania. No, I would be committing a crime if I did that, I was born in the wrong place to do that.

By then, I spoke English and was getting more experienced in my field each year. After years contacting hundreds of companies in Australia and doing remote test projects, I was offered a job with visa sponsorship, meaning I would get a temporary work visa to live in the "lucky country".

Everything worked out for me, and I've relocated permanently to Australia. But that was never the case for thousands of people who have contacted me in the last ten years asking for help to do the same. In fact, that's not the case for approximately one billion people in the world today.

Accordingly to a Gallup World Poll, 16% of the world's adults would like to move to another country permanently if they had the chance.

The point is: That same feeling I had about moving to Australia is not uncommon. Millions of people daydream about a similar move to a better country their entire lives. The sad part is that my migration story is an outlier. The vast majority of people are not able to legally enter the more developed nations due to current immigration law.

Removing (or at least reducing) immigration restrictions would not just be the right and moral thing to do. It would be one of the smartest and most impactful economic moves we could make.

It's practically unanimous between economists that reducing immigration restrictions would make the world more productive. To be more specific, estimates are we would instantly get close to doubling global GDP.

But if economic gains are so clear, why do countries decide to close their borders to foreigners?

I prefer not to enter the immigration debate directly linked to political elections around the world in the last couple of decades. People are too zoomed-in to see the big picture and think un-emotionally about at least small reductions in immigration restrictions that would create a net gain for most people.

The most frequent counter-arguments I hear are:

1) Mass migration would create mass poverty. A popular one is that everyone from South America and Africa would move to the U.S., which would, in turn, become a poor country.

2) No developed nation would be able to afford the new demand for their welfare programs. How would they keep a quality health system or unemployment protection program in place?

3) Terrorism.

4) The receiving countries would risk losing their national culture.

I can understand people raising these questions. It's just not productive that this is where they stop when they think about freer immigration. They are moved by fear and passion, and no healthy debate can come from that.

If you're interested in learning more about such questions, I highly recommend reading Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration.

Whatever your view and belief are about this topic, the truth is that at least small improvements can be made. The default logic for immigration law in 2020 is simply cruel.

One of the things that seem almost always to surprise people is knowing that having a passport and not being able to go to a country because of visa restrictions is a very recent phenomenon.

Until 1914, there were no travel restrictions based on where you were born. Anyone could go anywhere. Every individual could make their own decisions about where in the world they would be able to live a better life, as long as they had a way to make it to their desired destination.

And then came World War I, security concerns and the introduction of the modern passport as we know it. Germany, France and Italy were the first ones to officialise its use. By the end of the war, the system had global mass adoption.

The passport with visa restrictions was supposed to be a temporary "hack". For the next several decades, governments held international conferences to discuss getting rid of passports and restoring the freedom of movement for everyone.

But the temporary hack became a complex system with no easy way back. Less than a hundred years later, and we had all got used to it and could not imagine life without it anymore. No matter what, you have to agree we got used to critical loss of freedom.

I'm optimistic, and the good news is that if you zoom out, you can see the world is moving in the right direction on several fronts. There are still errors and injustices, of course, and the passport in its current form is an example. A mistake, I believe, that will be corrected slowly in the next few decades. I expect we will be talking about passport discrimination, the same way the world is currently talking about discrimination based on gender, skin colour or age, for example. No discrimination can be accepted, and as humans, I expect us to continue learning and evolving.

In the meantime, there's a lot more that could be done. A few examples: We could easily have at least ten times more free movement agreements between neighbour countries. The developed countries should be creating more flexible work-holiday programs, open to a much higher number of people than current volumes. And points-based immigration systems could be used as a way to start opening up the most strict and closed countries.

(Small agreement between Australia and Vanuatu in September 2020)

On a final note, our complex immigration programs, which change from country to country, create another substantial barrier: Access to information. I'm building Duoflag as a side project in a small attempt to have a centralised resource for people to discover and understand their options to migrate to another country. I wish this existed twenty years ago when I was researching my options. If this is something you're also interested in, I would love to hear from you and join forces.

--

Thanks to Abadesi Osunsade, Leticia Lamy and Bryan Caplan for reading drafts of this. Thanks to Dr Anton Howes for pointing out that passports did exist before 1914, but that most countries in the late 19th century had abolished them.